A reserve currency is a currency held in large quantities by other countries and banks as part of their financial reserves. A reserve currency is also often used to determine commodity prices on the global market (gold, oil, etc.) Currently, the main global reserve currency is the US dollar.

International Monetary Fund (IMF) data on the composition of foreign exchange reserves

USD

EUR

others

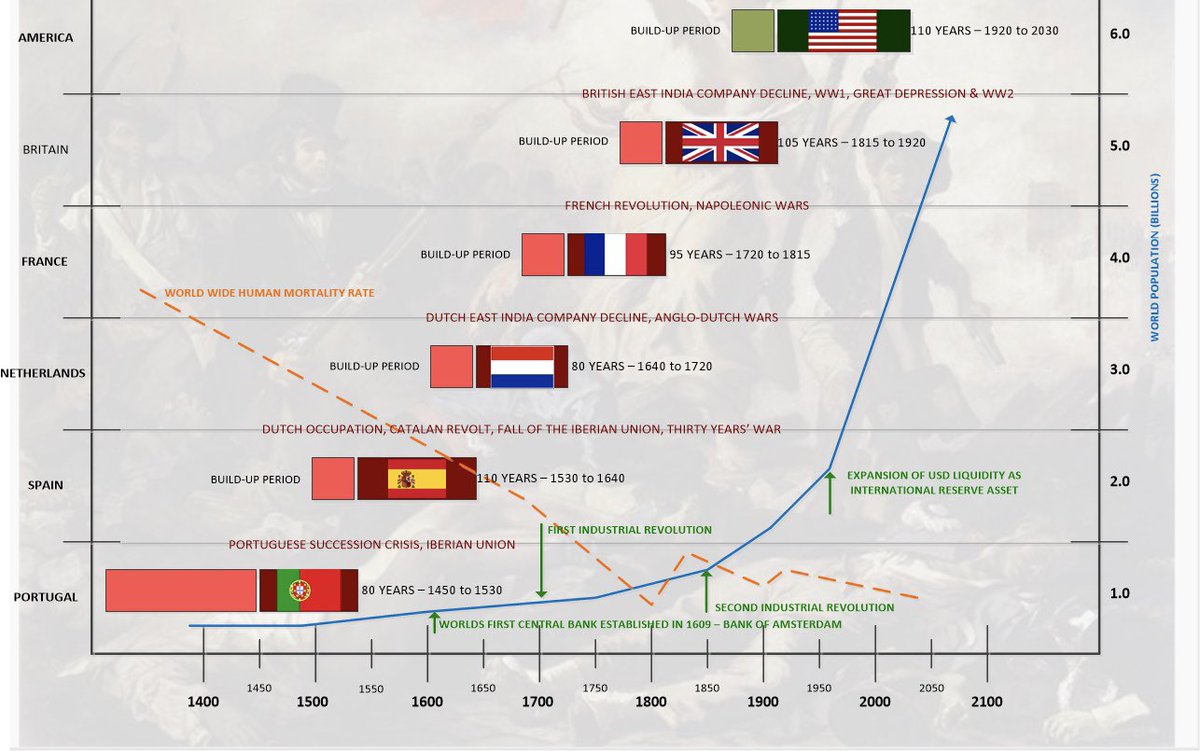

The world’s reserve currencies have changed in regular cycles over the past 600 years.

Evolution of World Reserve Currencies

All these countries controlled global trade. In the early days, they discovered new trade routes. Each of the countries was rich in something (slave trade, spice trade, etc.) at the given time, and had significant influence extending far beyond its borders. For example, Britain at its peak controlled up to a quarter of the world through its colonies.

What are the advantages for the country that issues the world’s reserve currency?

It saves on currency exchange when buying commodities (unlike other countries that first exchange their currency for the world’s reserve currency to buy those commodities), and it can borrow at a lower interest rate because its currency is in high demand. This country also has significant economic, cultural and, last but not least, political reach.

Portuguese Colonial Empire

The Portuguese Colonial Empire was the first truly global empire and the longest-lasting colonial empire in history—from the capture of Ceuta in 1415 to the handover of Macau to China in 1999.

Portugal became a global trading and maritime power during the 15th and 16th centuries, and by the end of the 17th century had acquired numerous colonies in Africa, America, India and Southeast Asia. The decline of the Portuguese Colonial Empire from the 17th century onwards was linked to the increased overseas involvement of the British, French and Dutch. The Portuguese were unable to effectively counter these more powerful nations.

Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire was one of the oldest and largest colonial empires in history. Spain pioneered overseas exploration in the 15th and 16th centuries, often establishing its own colonies in newly discovered territories. However, the vast territories in South America were acquired at the expense of the cultures already living there. Spain went on to build an extensive trading network.

Spain became a leading global superpower during the 16th century. The influx of gold and silver from its American colonies meant it could afford to maintain a powerful army and navy that dominated the world’s seas as well as European and American battlefields. Spanish culture also flourished at this time, and the 16th and 17th centuries have been called the Spanish Golden Age.

From the mid-17th century, however, the Spanish Empire began to lose strength. Spain finally lost its superpower status after the War of the Spanish Succession. The primary legacy of the Spanish Empire was the spread of Spanish as the mother tongue of the majority of the population of Central and South America and the spread of the Roman Catholic faith into the territories under Spanish rule. Many foodstuffs that are now commonplace in Europe were also brought from the Americas, including potatoes, corn, peppers, tomatoes, peanuts and tobacco.

Dutch Colonial Empire

The United Provinces of the Netherlands began constructing the Dutch Colonial Empire began around 1595-96, during the so-called Eighty Years’ War against the Spanish Empire. Unlike Spain and Portugal, however, the Netherlands, similar to e.g. Great Britain and Sweden, acquired new territories through specialised private companies (the most famous of which was the United East India Company). The Dutch first made trade and land lease agreements with local rulers, which later allowed them to buy up larger territories and create a monopoly on trade in exotic commodities (spices, precious fabrics and timber, various crops).

The 17th century saw great economic growth and the development of science and art. The Dutch also accounted for about half of global trade at this time, and the country became one of the world’s most important colonial powers.

With the political and economic decline of the mother country from the mid-18th century, the Dutch colonial empire gradually shrank in size, with the Dutch losing territory and bases to more predatory rivals, notably the British Empire.

After the French Revolution, Dutch provinces were seized by French troops in 1795. The French proclaimed the Republic of Batavia and later the Kingdom of Holland, which was annexed directly to Napoleonic France between 1810 and 1814.

French Colonial Empire

France acquired its first colonies in the early 17th century, eventually becoming one of the world’s decisive colonial powers.

From the mid-18th century to the early 19th century, the French Colonial Empire went through a difficult period of exhausting wars and internal conflicts that resulted in the loss of colonial territories. France ceased to be a global power after losing the Battle of Waterloo, and was replaced on the throne by Great Britain.

British Empire

The basis for Britain’s future overseas empire was its maritime policy. With victory over the Spanish Armada in 1588, England became one of the most important naval powers. Thanks to the extraordinary scale of the British Empire, English culture, the English legal system, traditional sports (e.g. cricket, rugby and football), the English system of measurement, education, and especially the English language itself—now the most widely spoken language—spread to many countries.

The British Empire was the largest colonial empire in human history. In 1921 it covered 33 million km², or about a quarter of the total land area of the planet.

Britain was also greatly helped by the Industrial Revolution (there were basically two: one in the 1700s and one in the 1850s). This allowed Britain to be much more efficient and achieve extremely low costs (for instance, the machine processing of cotton achieved production costs 500 times lower than the traditional method used in China).

The foundation of the USA also marked the end of the “First British Empire”. Expansion in North America was over, and Britain began to extend its power to other parts of the world. This led to the birth of the “Second British Empire” in Asia and Oceania and, later, in Africa.

The British Empire disintegrated in the decades following World War II, and most successor countries are now united in the Commonwealth of Nations. European colonial policy between about 1870 and 1914 is referred to as the New Imperialism. This period was characterised by the division of the entire world among the global superpowers.

United States of America

The English colonisation of the Atlantic coast was of the greatest importance to the history of the future United States. From 1664, England—and later the Kingdom of Great Britain—gradually took possession of Dutch and some French settlements in North America, creating 13 colonies on the coast by 1773. These became the foundation of the future USA.

Reckless interference by the mother country in the affairs of the colonies provoked anti-British opposition. One particularly notorious incident was the Boston Tea Party. Tensions culminated in 1775 with the outbreak of open war between the colonies and Great Britain. On 4 July 1776, the Second Continental Congress issued the Declaration of Independence, proclaiming the formation of the United States of America.

The massive economic development after the end of the Civil War made the USA the most economically powerful country in the world by 1872. Industrialists such as Cornelius Vanderbilt, John D. Rockefeller, Henry Ford, Andrew Carnegie, and banker John Pierpont Morgan were behind this boom in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The United States became one of the world’s superpowers at the beginning of the 20th century.

The 1920s brought another massive economic boom. American self-confidence was shaken by the Wall Street Crash of 1929, which caused a worldwide economic crisis that catalysed political developments in Europe in particular. In the United States itself, it led to the abandonment of pure “laissez faire” economic policies (i.e. no state involvement in private companies) and greater state intervention in the economy under the New Deal devised by Democrat President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

World War II was a very profitable business for the United States. They were paid by the Allied nations mostly in gold or territory. As a result, they accumulated two-thirds of the world’s physical gold during World War II. This was one reason why the Bretton Woods monetary system was adopted.

Until the start of World War I, the values of individual currencies were pegged to gold (for example, the US dollar was defined as 1/20th of an ounce of gold), and this peg made it impossible to issue new unbacked money. The enormous war expenditures led the combatants to abandon gold and engage in inflation because inflation is a kind of taxation, but one that—unlike a real tax—does not need to be publicly announced and can be implemented without the public’s informed consent. All major currencies were thus devalued, the dollar a little less so as the United States had entered the war later. After the end of World War I, neither side returned to the original standard.

In July 1944, at the Mount Washington Hotel in the Bretton Woods district of New Hampshire, USA, negotiations (in which Great Britain and the United States of America had the main say) were held between 44 countries on a new monetary system concept that could be introduced in the post-war world. The result was the Bretton Woods Agreement (also known as the dollar-gold equivalence standard) as the first global monetary constitution. The points of this conference were thought out two years in advance. The essence of the agreement was to link the US dollar to gold and all other currencies to the dollar. The dollar itself was pegged as 1/35th of an ounce of gold. However, only governments—not citizens—could exchange dollars for gold. The agreement was signed by all 44 participating countries and went into effect the following year, 1945.

The US dollar was given the status of official global reserve currency, from which the currencies of other countries would be derived. At the same time, the United States had to guarantee the convertibility of the dollar into gold at a fixed rate of USD 35 per troy ounce of gold (a form of gold standard). It was in the interest of the central banks of other countries to create sufficient foreign exchange reserves in US dollars. This retrospectively increased the attractiveness of this currency and strengthened its position in the post-war world.

The Bretton Woods agreement gave birth to the Stabilization Fund, later the International Monetary Fund, which began to supervise the newly created system. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (later the World Bank) was then founded.

Individuals could not convert dollars into gold, but the central banks of other countries could. As a result, the central bank of the United States (the Federal Reserve) was obliged to exchange a supplied amount of dollars for a corresponding amount of gold at the request of banks of other countries. However, successive United States governments gradually produced more and more paper money than would correspond to this exchange rate. Other countries, particularly France, responded by demanding the exchange of dollars for gold, leading to withdrawals of the gold held by US banks from US territory, and the United States lost its monetary gold. As the USA had substantial gold reserves after World War II, the system held up for quite a long time, but had begun to crumble by the late 1960s.

The United States responded in March 1968 with an arrangement whereby US monetary gold was to be traded completely separately (still at a price of USD 35 per ounce) from gold on global markets. Other governments committed not to sell or buy this gold elsewhere. In August 1971, when France and Great Britain requested that the Bretton Woods Agreement be fulfilled, the then President Richard Nixon did not comply and abolished the Bretton Woods system by “closing the gold window” on 15 August. This led to an era of floating exchange rates. Within months of the end of the Bretton Woods Agreement, the price of gold had risen tenfold.

Spain’s currency was the world’s reserve currency for the longest time: exactly 110 years. The US dollar has been on the throne since 1920, and so it may be in the last decade of its reign.

What currency will replace the US dollar? Will it be a digital currency? Or perhaps one backed by gold? Follow our website to be among the first to know.